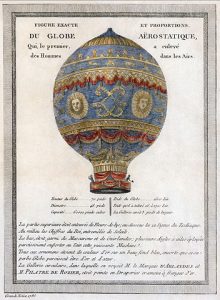

Paris, 1783: The First Manned, Untethered Hot Air Balloon Flight

On November 21, 1783, chemistry teacher Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and aristocrat François Laurent d’Arlandes took to the skies over Paris in the first manned, untethered hot air balloon flight, and launching themselves into the history of hot air ballooning. Their craft was a linen balloon and wicker gondola, designed by aerostatic flight pioneers Etienne and Joseph Montgolfier.1 While it wasn’t the first balloon to ascend without a tether (in fact, another Montgolfier balloon was sent up in Annonay with livestock inside, only weeks before2), it was the crucial catalyst for not only balloon flight, but the craze that brought air travel as a whole into the realm of possibility.

Man’s fascination with flight was not exclusive to the Montgolfier brothers, nor new to their time: ancient Chinese cultures had long perfected the art of kite-flying, and even the legend of Daedalus—the young man who flew too close to the sun and melted his makeshift wings—resonated with commoners and aristocrats alike.3 The Renaissance, in particular, contributed greatly to modern aviation. Leonardo da Vinci’s early inventions often incorporated elements of flight; Isaac Newton’s discovery of gravity and subsequent research paved the way for new innovations, and a much more comprehensive understanding of aerodynamics.4

In 1709, several decades before the Montgolfier flights, Bartolomeu de Guomao of Lisbon allegedly ascended in a balloon with parts reminiscent of a bird. Documentation was severely lacking, however, and it is not recognized as an official flight.5 It wasn’t until the Montgolfier brothers, rich paper manufacturers from the south of France, took an interest in thermal airships that the movement gained momentum.

The inspiration for constructing hot air balloons came years before, when Joseph noticed laundry billowing over a fire due to pockets of hot air forming and rising. The brothers’ earliest ships were made with taffeta and other lightweight fabrics; test flights were tethered and unmanned, consisting of balloons and heat sources, yet lacking galleries to carry passengers.6 After the successful manned flight in Paris in 1783, these airships became known as “Montgolfier balloons,” and remained in use for hundreds of years. While modern designs have changed, most balloons still resemble the famous Montgolfier model.

The flight, while successful, was nerve-wracking for Laurent d’Arlandes, who noticed holes in the linen and became worried. His companion, Pilâtre de Rozier, was unfazed, instructing Laurent to keep stoking the fire with bundles of hay and thin sticks, so that they might rise above Paris and find a safe place to land outside of the city. A detailed account by Benjamin Franklin, who watched the flight with fascination, describes the mechanism of the balloon quite well:

“The persons who were plac’d in the gallery made of wicker, and attach’d to the outside near the bottom, had each of them a port thro’ which they could pass sheaves of straw into the grate to keep up the flame, and thereby keep the balloon full. When it went over our heads, we could see the fire which was very considerable. As the flame slackens, the rarefied air cools and condenses, the bulk of the balloon diminishes and it begins to descend. If those in the gallery see it likely to descend in an improper place they can, by throwing on more straw, and renewing the flame, make it rise again, and the wind carries it further.”7

Just two months later, other balloon voyages commenced—some with several passengers, reaching heights of three thousand feet or more. Helium and hydrogen airships gained traction, as well: predecessors to modern rigid airships and blimps. By 1785, “aerostatic machines,” as balloons were known, peaked, after the first men crossed the English Channel.

As new flight technologies emerged the following year, however, public interest and formal research on hot air balloon travel and construction declined to almost nothing.8 Despite this, select groups, now including people overseas in the United States, as well as all across Europe, remained fascinated with the idea, and kept ballooning alive through the centuries.

In a way, the history of hot air ballooning mimics the locomotive industry: once a worldwide trend, yet now more recreational than anything else to the general public. It differs, however, in that balloon travel continues to expand, such as the emerging industry of suborbital flights.9 Traditional ballooning is also adopted by many parachutists and skydivers, who prefer scenic ascents over quick jetliner flights.10

Today, the Montgolfier legacy lives on. Ballooning remains one of the top ranked things to do by tourist offices worldwide. Hot Air Balloon rides today occur on six of the seven continents (Asia, Africa, the United States, Europe, South America, and Australia) international tourists enjoy balloon rides in high profile ballooning locations such as in Chile with balloon company Atacama11, and in Australia with Cairns company like Hot Air Balloon Cairns12 and Balloons Over Brisbane.

Cited

1 New Space Frontiers: Venturing into Earth Orbit and Beyond. Piers Bizony, published by Zenith Press of Quarto Publishing Group USA, INC. 2014.

2 “Man’s first aerial flight,” E.C. Watson. Engineering and Science. May 16, 1949. http://calteches.library.caltech.edu/993/1/Flight.pdf, accessed November 4, 2016.

3 A Light History of Hot Air. Peter Doherty, published by Melbourne University Press. 2007.

4 Ibid.

5 The Montgolfier Brothers and the Invention of Aviation, 1783-1784. Charles Coulston Gillispie, published by Princeton University Press. 1983.

6 Ibid.

7 “Man’s first aerial flight,” E.C. Watson. Engineering and Science. May 16, 1949. http://calteches.library.caltech.edu/993/1/Flight.pdf, accessed November 4, 2016.

8 “Ballooning in France and Britain, 178301786: Aerostation and Adventurism,” Richard Gillespie. Isis, Vol. 25, No. 2. Published by the University of Chicago Press, June 1984.

9 New Space Frontiers: Venturing into Earth Orbit and Beyond. Piers Bizony, published by Zenith Press of Quarto Publishing Group USA, INC. 2014.

10 Ibid.

11 See http://easternsafaris.com/balloonsoveratacama_home

12 See http://www.hotair.com.au/cairns

Image list

Image 1

By Sequajectrof – Jacques Forêt (Own work) CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons Image 2

Image 2

By Unknown – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress‘s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID ppmsca.02447.This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing for more information., Public Domain, Link.

Image 3

Three men are in the basket of a hot-air balloon, with ropes – see page for author [CC BY 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

Image 4

Balloons Over Brisbane fly daily all year round in Queensland, Australia.